Nr. 1

Nr. 2

Nr. 3

Nr. 4

Nr. 5

Nr. 6

Nr. 7

Nr. 8

Nr. 9

Nr. 10

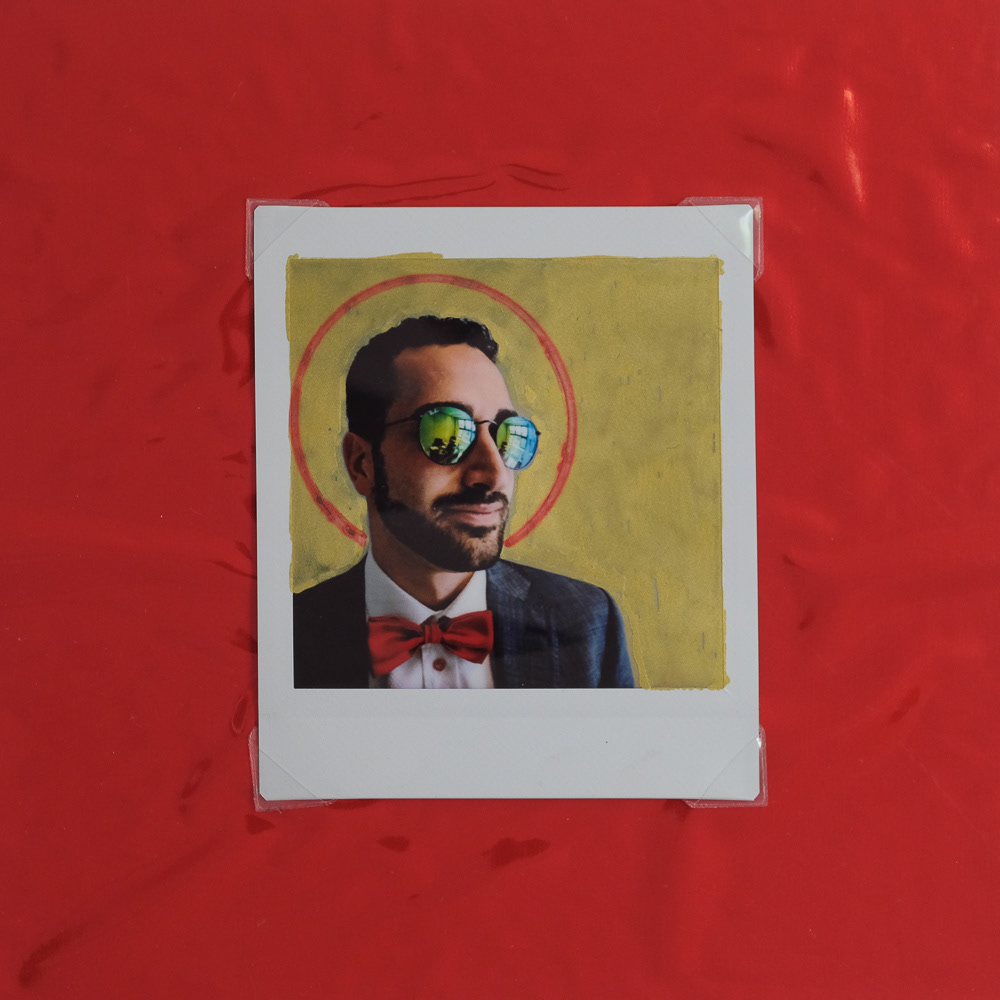

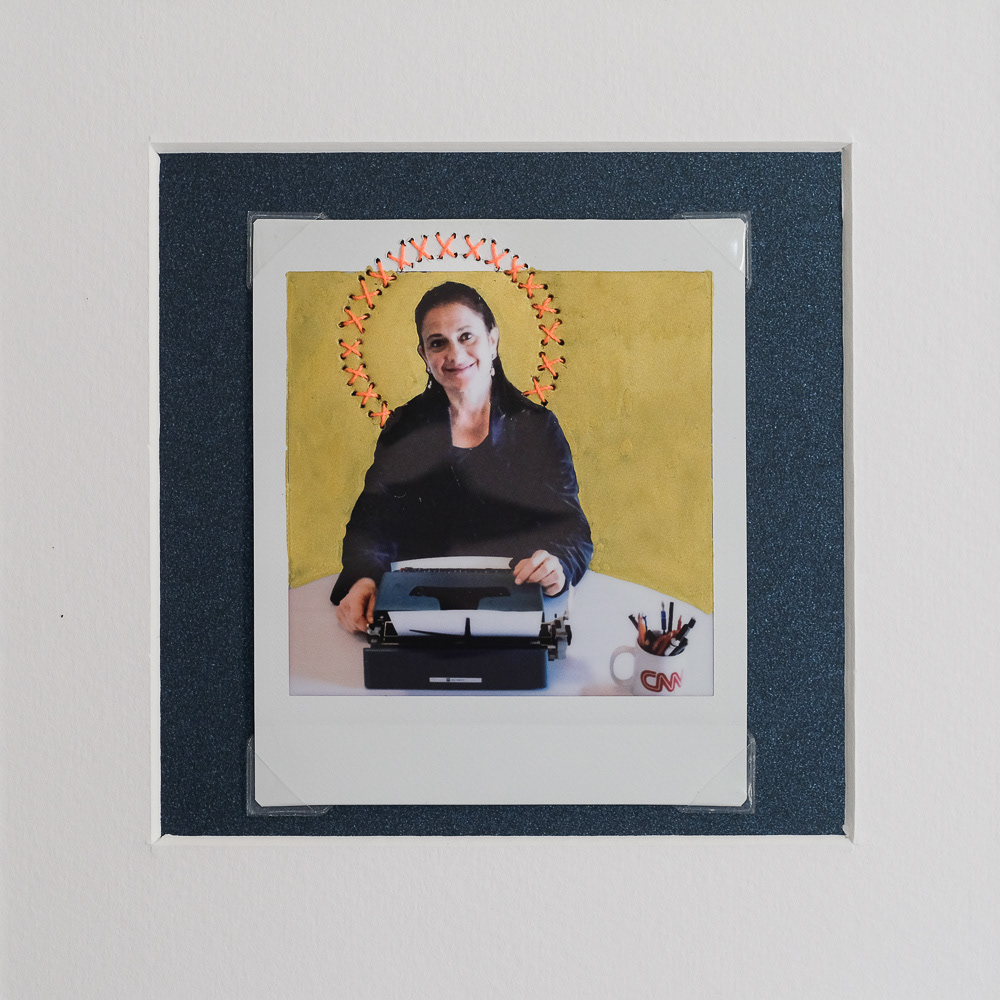

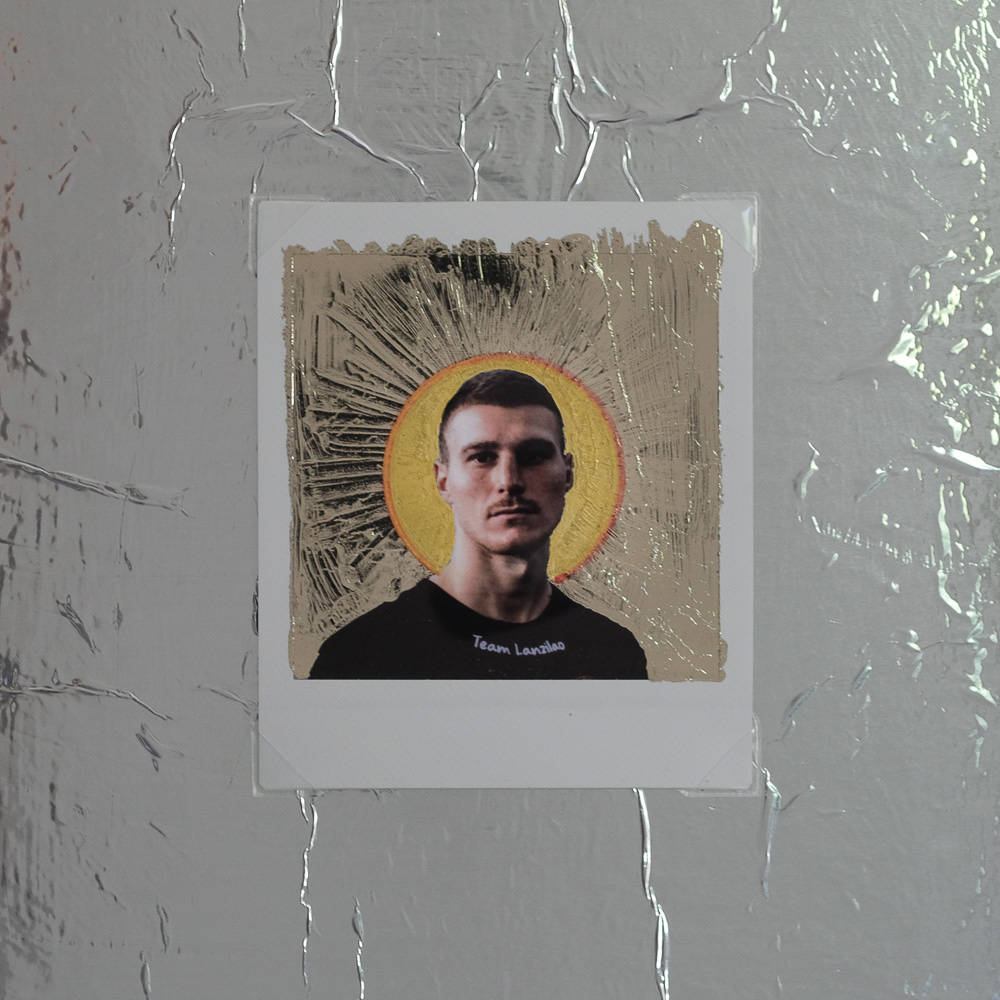

In the Byzantine tradition, icons are considered 'windows on the mystery', images (in Greek 'eikon' means 'image, figure') endowed with extraordinary faculties and destined for prayer. Venerating them means being able to know and venerate the reality of those depicted in them - God, the Mother of God, the Saints - and has a salvific value.

Giovanni Battisti's 'Secular Icons' also have a faculty that is out of the ordinary: they remind us that we can all, without distinction, draw on something precious and unique, a 'golden seed' that dwells in each of us, ready to germinate, provided we want it.

The idea of creating a gallery of 'icons' dedicated to the potential of every human being was born as a direct consequence of the IMAGO DIGNITATIS project. As Giovanni himself says, "I wanted to create something new, starting from scratch, so I spent a lot of time questioning myself on the meaning of the word dignity, very often linked to contexts of poverty, illness, discomfort and redemption. The semantic declination he has chosen departs from this nuance of meaning and goes beyond the boundary of any contingent accidentality, with the intention of capturing the 'primal' meaning of dignity, free of other implications, to represent its living core.

From this idea come the first portraits, dedicated to children: examples of the highest dignity because they are closest to the 'initial' state of purity and integrity. The halo, deliberately always present to crown the head of the subjects, has precisely the function of making visible the 'high' potential for the development of the self, linked to the profound dimension inherent in every human being. The halo, Giovanni explains, is a warning - 'Remember what you can be' - an encouragement to keep oneself 'worthy of dignity', a call to actively live it.

To create his 'album of icons', he chose to turn each photograph into a unique piece, like those who are the protagonists, intervening on the print in a new and different way each time. The only constant is the use of the Fujifilm Instax printer which allows, starting from digital files, to obtain Polaroid format photographs. A type of photo accessible to all that brings to mind the unpretentious family albums of the 1960s and 1970s, but also associated with unconventional artistic manipulation and experimentation. Invented in 1937 by Edwin Land after many years of research, the first instant camera - the Polaroid 95 - saw the light in 1948 and was immediately a great success. Its diffusion went viral, but what made it a cult object in the artistic sphere was mainly Andy Warhol who, from the late 1960s onwards, made maniacal use of it, using it not only as a constituent element of his works but also as a tool to preserve the memory of each moment: 'That's why I take photographs. It is a visual diary,' he explained.

The choice of the Polaroid format implicitly positions 'Secular Icons' in a Pop matrix expressive panorama, a sphere in which the icon becomes a pivotal element. But Giovanni also retains a clear and direct link with Byzantine prototypes, small-format tablets in which gold pervades space like a supernatural light. Even in the executional care, which takes a long time to reach the final outcome, there is an explicit memory of that tradition. Giovanni recounts that his work starts from both mobile phone and camera shots and, once he has obtained the Polaroid, he works on each portrait 'responding' instinctively to expressive needs that he feels are closely linked to the individual subject, needs that guide him in the fine-tuning of the execution methods and the selection of materials. The gold is sometimes in leaf, other times a simple felt-tip pen; the backgrounds on which he fixes the Polaroid are different papers, in addition to gift wrapping paper, there is newspaper, transferred, however, through the use of trichlorethylene; even the application of colours denotes different procedures; only once for the background did he choose fabric: a white Procida linen, a tribute to his mother-in-law Autilia; just as only for the portrait of his wife did he measure himself with weaving to realise the halo: a technical complexity that required time and attention, almost a restitution for the care Enza devoted to the family.

One would say that for Giovanni there is a real need to give voice to the uniqueness of each person through the creative process. It is no coincidence that the subjects chosen so far are part of his life: his parents, his children, his wife, his much-loved mother-in-law, chosen friends, a colleague and a few others. Living memories. Relationships are a founding ingredient for him, a kind of yeast, invisible but indispensable for creating a true family album, which is however only the incipit of an open project, destined to enrich and expand over time.

The dignity to which Giovanni intends to give visibility and prominence is inherent in our human being, and precisely for this reason he looks us straight in the eye and interrogates us with the pressure of a daily question and with the boldness of one who has no problem asking what he wants to know. It is a dignity stripped of all trappings, reduced to the core of the matter: being here - today more than ever - constantly positions us at a crossroads. On the one hand, there is the slide of forgetting what we could be, on the other, there is the springboard to exploit that potential and make it concrete, watering it every day with the care that is devoted to a rare seed to ensure that it comes to bear its precious fruit. A gamble that concerns us all and whose outcome has much to do with the future.

Giovanni Battisti's 'Secular Icons' also have a faculty that is out of the ordinary: they remind us that we can all, without distinction, draw on something precious and unique, a 'golden seed' that dwells in each of us, ready to germinate, provided we want it.

The idea of creating a gallery of 'icons' dedicated to the potential of every human being was born as a direct consequence of the IMAGO DIGNITATIS project. As Giovanni himself says, "I wanted to create something new, starting from scratch, so I spent a lot of time questioning myself on the meaning of the word dignity, very often linked to contexts of poverty, illness, discomfort and redemption. The semantic declination he has chosen departs from this nuance of meaning and goes beyond the boundary of any contingent accidentality, with the intention of capturing the 'primal' meaning of dignity, free of other implications, to represent its living core.

From this idea come the first portraits, dedicated to children: examples of the highest dignity because they are closest to the 'initial' state of purity and integrity. The halo, deliberately always present to crown the head of the subjects, has precisely the function of making visible the 'high' potential for the development of the self, linked to the profound dimension inherent in every human being. The halo, Giovanni explains, is a warning - 'Remember what you can be' - an encouragement to keep oneself 'worthy of dignity', a call to actively live it.

To create his 'album of icons', he chose to turn each photograph into a unique piece, like those who are the protagonists, intervening on the print in a new and different way each time. The only constant is the use of the Fujifilm Instax printer which allows, starting from digital files, to obtain Polaroid format photographs. A type of photo accessible to all that brings to mind the unpretentious family albums of the 1960s and 1970s, but also associated with unconventional artistic manipulation and experimentation. Invented in 1937 by Edwin Land after many years of research, the first instant camera - the Polaroid 95 - saw the light in 1948 and was immediately a great success. Its diffusion went viral, but what made it a cult object in the artistic sphere was mainly Andy Warhol who, from the late 1960s onwards, made maniacal use of it, using it not only as a constituent element of his works but also as a tool to preserve the memory of each moment: 'That's why I take photographs. It is a visual diary,' he explained.

The choice of the Polaroid format implicitly positions 'Secular Icons' in a Pop matrix expressive panorama, a sphere in which the icon becomes a pivotal element. But Giovanni also retains a clear and direct link with Byzantine prototypes, small-format tablets in which gold pervades space like a supernatural light. Even in the executional care, which takes a long time to reach the final outcome, there is an explicit memory of that tradition. Giovanni recounts that his work starts from both mobile phone and camera shots and, once he has obtained the Polaroid, he works on each portrait 'responding' instinctively to expressive needs that he feels are closely linked to the individual subject, needs that guide him in the fine-tuning of the execution methods and the selection of materials. The gold is sometimes in leaf, other times a simple felt-tip pen; the backgrounds on which he fixes the Polaroid are different papers, in addition to gift wrapping paper, there is newspaper, transferred, however, through the use of trichlorethylene; even the application of colours denotes different procedures; only once for the background did he choose fabric: a white Procida linen, a tribute to his mother-in-law Autilia; just as only for the portrait of his wife did he measure himself with weaving to realise the halo: a technical complexity that required time and attention, almost a restitution for the care Enza devoted to the family.

One would say that for Giovanni there is a real need to give voice to the uniqueness of each person through the creative process. It is no coincidence that the subjects chosen so far are part of his life: his parents, his children, his wife, his much-loved mother-in-law, chosen friends, a colleague and a few others. Living memories. Relationships are a founding ingredient for him, a kind of yeast, invisible but indispensable for creating a true family album, which is however only the incipit of an open project, destined to enrich and expand over time.

The dignity to which Giovanni intends to give visibility and prominence is inherent in our human being, and precisely for this reason he looks us straight in the eye and interrogates us with the pressure of a daily question and with the boldness of one who has no problem asking what he wants to know. It is a dignity stripped of all trappings, reduced to the core of the matter: being here - today more than ever - constantly positions us at a crossroads. On the one hand, there is the slide of forgetting what we could be, on the other, there is the springboard to exploit that potential and make it concrete, watering it every day with the care that is devoted to a rare seed to ensure that it comes to bear its precious fruit. A gamble that concerns us all and whose outcome has much to do with the future.

(Text by Francesca Boschetti, graphics specialist for the Contemporary Art Collection of the Vatican Museums.)